According to StarCare, opioid use is a rising issue in Lubbock.

In order to educate the public, StarCare partnered with Lubbock Public Health’s Prevention Resource Center to provide a presentation on the history of the opioid epidemic in the U.S., risk factors for opioid use, and how to recognize and respond to an opioid overdose.

Ariea Alexander is the opioid use disorder outreach specialist for StarCare. She said there are multiple aspects that go into raising awareness of the dangers.

“We're kind of fighting two monsters at the same time,” she said. “We're finding people who are kind of in denial about saying that we do have a problem. At the same time, we have these people on the other side who are actually using these substances.”

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there have been three waves of opioid overdose deaths. The first wave was a rise of opioid deaths from prescribed opioids in the 1990s. In 2010, the second wave began with “rapid increases of opioid deaths involving heroin.” And the third wave began shortly after in 2013, when there was an increase of deaths from synthetic opioids, like fentanyl.

According to the C.D.C., many opioid deaths today also involve other drugs. And Alexander said “deceitful practices” from drug dealers have resulted in stronger opioids getting mixed in with other substances.

“Especially what we see at StarCare, like from our [Medication Assisted Treatment] clinic,” she said. “When we do the drug test, people say, ‘Oh, well, I do heroin. I don't do fentanyl.’ And that may be true, but it's getting put in there.”

Prescription opioids can also be dangerous. Alexander said the human body can become dependent on prescription opioids after seven days.

Alexander also said there is a distinction between ”dependence” and “tolerance,” even though they are often used interchangeably.

She said dependence is needing a drug in order to “feel normal.” While tolerance is needing more of a substance in order to get the same feeling you did the first time you used it.

Even those who are using opioids as prescribed should keep an eye out for withdrawal signs when they are taken off that medication and should contact a doctor if they notice symptoms like anxiety, insomnia, restlessness, or muscle aches.

The best way to avoid opioid misuse, and to keep them from winding up in the wrong hands, is to properly dispose of medication once your prescribed use has ended.

Alexander said medications should not be flushed down the toilet or thrown in the trash. She said they can be brought back to the pharmacy, thrown away in a drug deactivation pouch, or at medication cleanouts hosted by local health entities.

Fentanyl is a prescription medication and can be used properly under the direction of a doctor, but much of what can be found in the drug market is illicitly manufactured.

In her presentation, Alexander addressed some common fentanyl myths.

Fentanyl cannot be absorbed through the skin by touch, unless it were to get into an open wound. Powdered opioids do not aerosolize, so it is also highly unlikely for it to be inhaled through the air due to proximity.

While fentanyl is 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine, more potent opioids are not more dangerous for first responders.

“I think that's more of a hot topic, just because there's been videos of cops coming to an encounter with it and they're having this reaction, but it's really just them having a panic attack,” Alexander explained. “We actually spoke to an officer the other day, he kind of mirrored the same thing. He was in a situation, he got fentanyl on him, he started freaking out, because he knows the dangers of it. But he's like ‘I had to calm myself down. I was like, No, you're just freaking out. You're fine.’”

Alexander stressed that anyone is at risk for an opioid overdose, but some of the risk factors include co-occurring mental or physical health conditions, feeling a lack of connection to family or community, and a history of past overdose.

When it comes to actual opioid use, the factor with the highest chance of resulting in death, according to Alexander, is using opioids alone.

“If you’re using alone and you overdose, who’s going to say anything?” Alexander said.

Some classic signs of an opioid overdose include cold or clammy skin, dizziness or disorientation, unresponsiveness, slow breathing, choking or snoring sounds, small pupils, and discoloration of the lips and nails.

Complex signs of an overdose could be involuntary and uncoordinated movements, muscle rigidity, and prolonged sedation – or a return to normal breathing but with maintained unresponsiveness.

Overdoses are not always sudden and can happen minutes or hours after taking opioids. Often, there are three stages to an opioid overdose.

The first stage has shallow breathing and a drowsy appearance, but awareness when addressed or touched.

In the second stage, breathing may slow further and the person may start to nod off.

A person in the third stage may not be breathing at all and/or they might be making snoring sounds, they may be unresponsive, even to painful stimuli.

If you find someone experiencing an overdose, Alexander gave the steps for responding.

First, check for responsiveness. “Shout their name, tap them on the shoulder, or give a sternum rub," she instructed. "You make a fist, you find their breastplate, and you can either rub as hard as you can, up and down or in a circular motion.”

The next step is to put someone in the recovery position and call 911.

Even if you administer Naloxone, Alexander stressed the importance of calling 911 as well.

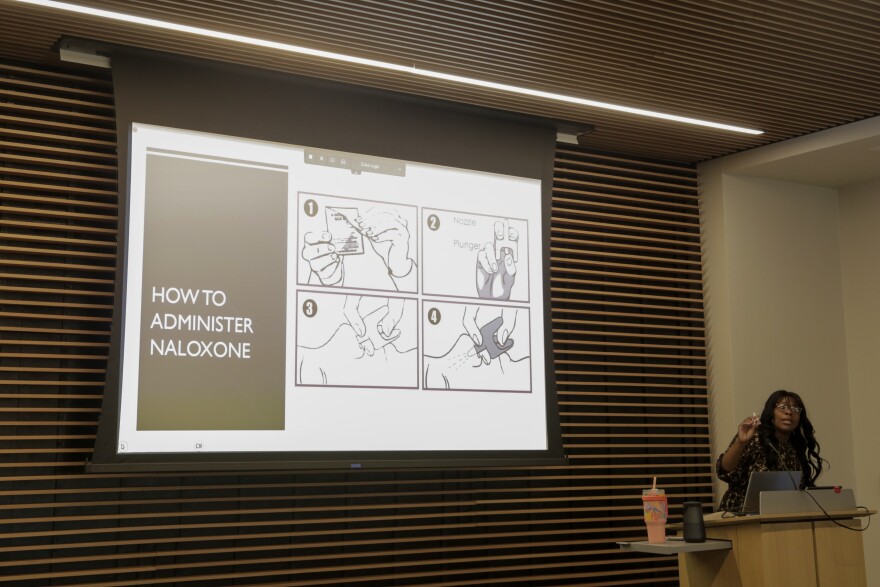

Naloxone, better known by the name brand Narcan, is a medication that can reverse an opioid overdose.

Naloxone is available in injectable and nasal spray forms. At the event, LPH gave out Naloxone nasal spray kits, which are available at pharmacies without a prescription.

Naloxone works in one to three minutes and lasts 30 to 90 minutes. Alexander explained that the medication essentially “kicks the opioids off” of receptors that opioids bind to, and allows the person to breathe.

“Naloxone is not treatment. It's just something to hold someone over until they can get medical treatment,” Alexander said. “So don't think, ‘Well, I gave them some Naloxone, they're fine.’ No, because after that 30-90 minutes, [it] wears off, they can overdose again.”

According to Alexander, Naloxone is safe for anyone, including children and those who are pregnant.

Naloxone has a long shelf-life and can endure extreme temperatures, like if it is left in a car.

If the person still is not breathing after following the instructions on the Naloxone kit, Alexander said the next step is to begin CPR, or rescue breathing. She said to place them on their back, tilt their chin to open their airway, plug their nose, and breathe into their mouth until you see their chest rise, then repeat a strong breath every five seconds until they resume breathing.

Alexander said the final step is to monitor them until emergency services arrive. She said not to leave a person after administering Naloxone, although she said they are likely to be unhappy and view the reversal as “ruining their high.”

If a person has come back from an overdose, do not let them eat, drink, or take more opioids.

“I know opioids can be really scary, but please don't leave someone who is overdosing because they do need your help,” Alexander said.

Alexander said that while there are “Good Samaritan” laws to protect people who call for emergency aid, there are limitations in the state of Texas.

If you are a first responder or medical professional, there are different rules because you are expected to know how to respond in an emergency situation.

You also may not be protected by the Good Samaritan laws if you have a felony record or if you have called 911 for an overdose within a previous 18-month window.

Alexander encouraged people to educate themselves and carry Naloxone just in case, even if they don’t think they’ll be in a situation to use it.

“It's better to have the education, have the tools to respond to opioids, then find yourself in a situation where you need it and you don't have it,” she said. “Do what you want to do, but this is something that's happening, and it's better to be prepared before it comes knocking on your door.”

You can contact Lubbock Public Health for additional information on Naloxone kits, as well as prevention and substance use resources at 806-775-2933.

Lubbock Public Health's Substance Use Service Assistance Network, or SUSAN, provides transportation, financial assistance, medical services, personal hygiene, educational employment needs, sober housing, as well as assistance in harm reduction.

StarCare also provides education and outreach; substance use assessment, screenings, and referrals; recovery and treatment support; an outpatient program; and its Medications for Opioid Use Disorder program.

You can find a list of substance use resources from Prevention Resource Centers District 1 – which covers 41 counties including Lubbock, Hale, Hockley, Bailey, and Lamb – here.