Across the South Plains, traces of Indigenous history remain — in the stories families pass down and in the land that once sustained entire nations. For many Native people in West Texas, those traces are more than memory. They’re reminders of a presence that endures.

For Cyndi Slaughter, founder of Native American People of the Plains and Beyond, those stories are the heart of her work. Her nonprofit’s mission is to educate and unite communities through recognition and cultural exchange — work she says is long overdue.

Texas officially recognized the second Monday in October — a day that’s been celebrated as Columbus Day in America for almost a century — as Indigenous Peoples Day in 2021. Another thing Cyndi says was overdue, but something she’s still grateful for.

“We were here before you-know-who decided to come over and take charge,” Slaughter said. “It means so very much for the people to be recognized, finally. They have been pushed to the bottom of the pile so often that it’s almost impossible for any of us to stand up and proudly say that we are Native American …

“but to have Texas stand beside us and acknowledge the fact that we are here — we're still here —means everything to us as a people.”

Though Native people represent a small portion of the population in the region — just over 1 percent in Lubbock County, according to the U.S. Census Bureau — their cultural impact stretches far beyond the numbers. Slaughter said visibility is key to survival, and celebration is one of the most powerful tools.

Her group is now planning a major powwow for 2026, the first large-scale event of its kind in Lubbock since 2012. The celebration will gather tribal dancers, veterans, artisans and food vendors from across Texas and beyond.

“You're going to see so many different tribal affiliations. The dancers that do go out and dance, they're all representing their heritage, and every group is different,” Slaughter said.

"It's a wonderful experience, because it does give people an inside look at who we are.”

For Slaughter, celebration and education go hand in hand — a chance not only to give insight into a culture, but to correct the myths that have long overshadowed it.

"It's still not taught as it should be, and that's just the truth,” Slaughter said. “The children are still dressed up, you know, they put on their Thanksgiving, you know, holiday thing, and they dress like the Native Americans. And you know that Columbus is so good and you know, and they just celebrate it. It's not really being taught for what it really is.”

She keeps a binder full of broken treaties — a record of promises made and forgotten — as a reminder that history isn’t something to move past, but something that continues to shape Native lives.

“I think that our government truly needs to go back and go from the very beginning and see what’s been done to Native American people,” Slaughter said. “If they would just go back and give the truth and stop trying to take things away, and just realize that the Native American people are still here.

“Native American people could teach on the ecosystem. They could teach the importance of our prairies and our mountains and our waterways and so many things, because it's still so ingrained in them. They understand how to do that, but nobody will really listen, and nobody will really go back and explore what's really happened since Columbus stepped foot on this country, on this soil.”

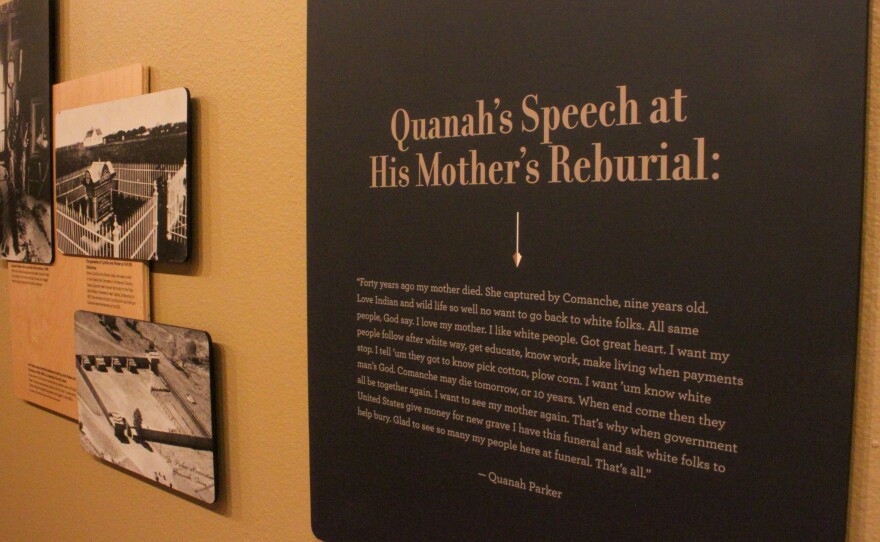

That sense of reconnection is what drives Ken LeBlanc, a 77-year-old resident of Post, Texas, whose wife, Shirley, is Comanche. He recalls when Bruce Parker, great-grandson of legendary Comanche leader Quanah Parker, visited the National Ranching Heritage Center to bless beadwork that once belonged to Quanah.

He shared a conversation he had with Parker about a scenic overlook in Post where visitors can gaze off the caprock.

“He said, ‘I had never been there before, I came across there and I started crying,’ he said. “You look out there, and you realize that you could look 360 degrees, and everything you see at one time was Comanche,” LeBlanc described.

LeBlanc said that for many families, identity is rediscovered rather than inherited. He says his wife didn’t remember she is Comanche until her sister shared old family stories.

Remembrance is why he now spends much of his time making beaded necklaces to sell at powwows — a quiet way to keep the craft alive.

And while Slaughter has her binder of broken promises, Leblanc has his ceremonial smoking pipe, which he held firmly in his hand for most of our interview.

“Indians do not take that smoke into their lungs. It's called kinikinik, and it's herbs as well as tobacco. They say their prayers, they take it into their mouth, and then they blow that out to God, and it carries their prayers to God,” LeBlanc said.

“This thing here has caused more deaths than anything else between Native Americans and Euro-Americans. The reason why is: to the Europeans, it was just an old pipe. To the Indians, this is sacred, and if you make a promise on this, you better keep it. And the Europeans never understood that.”

Across Texas, there are roughly 268,000 people who identify as American Indian or Alaska Native — a small but vibrant 1 percent of the state’s population. Another 247,000 Texans identify as both Native and white, and 46,000 as Native and Black, according to data from Every Texan. Many believe those figures undercount Indigenous Texans, especially those who live in rural areas or have mixed heritage.

For Slaughter, those numbers tell a story of quiet endurance — one she hopes to make louder.

“You know, we're not all brown-skinned. We're not all, you know, dressed in buckskin and, you know, bows and arrows. We all look different, but we're all still here,” Slaughter said. “And I think that it would just be wonderful if they would just get a sense of curiosity to send them out on the first adventure in the first place and then go on from there, they would be really surprised.”

In 2012, Slaughter attended the last powwow held near Lubbock — a small but powerful gathering in a barn near Buffalo Lake. It was there she received her Native name, Mazaska Itsa, meaning “Golden Eyes.”

The event stayed with her for years.

“I wrestled with, should we try to bring this back? Should we do anything about this? And I went to my husband and I said, ‘Rex, it’s just weighing on my soul. We need to bring this back to Lubbock,’” Slaughter said.

“We've got new people here. They've never experienced it. They've never known anything about it, and that's what we're trying to do.”

Since then, her organization has become a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, supported by the Lubbock Cultural Arts Foundation and Civic Lubbock. Her dream is for the 2026 powwow to become an annual tradition — one that restores the connection between Indigenous culture and the land that once sustained it.

For Slaughter, LeBlanc and others across the South Plains, these efforts are more than remembrance. They’re reclamation — a way to remind their neighbors that Native history isn’t something buried in textbooks, but living and breathing right here on the high plains of West Texas.

“We're trying to bring recognition, not only to the people, but also an experience for the general public to understand," Slaughter said. "This is who we are. We're still here. We're inviting you to come in and experience it with us.”